Victorian London on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

During the 19th century,

During the 19th century, London was transformed into the world's largest city and capital of the

During the 19th century, London was transformed into the world's largest city and capital of the

accessed 15 September 2020 This Marine Police Force, regarded as the first modern police force in England, was a success at apprehending would-be thieves, and it was made a public force via the Depredations on the Thames Act 1800.Marine Police History

accessed 15 September 2020 In 1839 the force would be absorbed into and become the Thames Division of the Metropolitan Police. In addition to theft, at the turn of the century commercial interests feared the competition from rising English ports like With the eclipse of the sailing ship by the

With the eclipse of the sailing ship by the

Suburbs were aspirational for many, but also came to be lampooned and satirised in the press for the conservative and conventional tastes they represented (for example in '' Punch's'' Pooter). While the Georgian terrace has been described as "England's greatest contribution to the urban form", the increasing rigour with which Building Act regulations were applied after 1774 led to increasingly simple, standardised designs, which by the end of the 19th century were accommodating many households at the lower end of the socio-economic scale. Indeed, more grandly designed examples became less common by this period, as the very wealthy tended to prefer detached homes, and terraces in particular now became associated first with the aspirational middle classes, and later with the lower middle classes in more industrial areas of London such as the East End.

While many areas of Georgian and Victorian suburbs were damaged heavily in

Suburbs were aspirational for many, but also came to be lampooned and satirised in the press for the conservative and conventional tastes they represented (for example in '' Punch's'' Pooter). While the Georgian terrace has been described as "England's greatest contribution to the urban form", the increasing rigour with which Building Act regulations were applied after 1774 led to increasingly simple, standardised designs, which by the end of the 19th century were accommodating many households at the lower end of the socio-economic scale. Indeed, more grandly designed examples became less common by this period, as the very wealthy tended to prefer detached homes, and terraces in particular now became associated first with the aspirational middle classes, and later with the lower middle classes in more industrial areas of London such as the East End.

While many areas of Georgian and Victorian suburbs were damaged heavily in

The East End of London, with an economy oriented around the Docklands and the polluting industries clustered along the Thames and the

The East End of London, with an economy oriented around the Docklands and the polluting industries clustered along the Thames and the

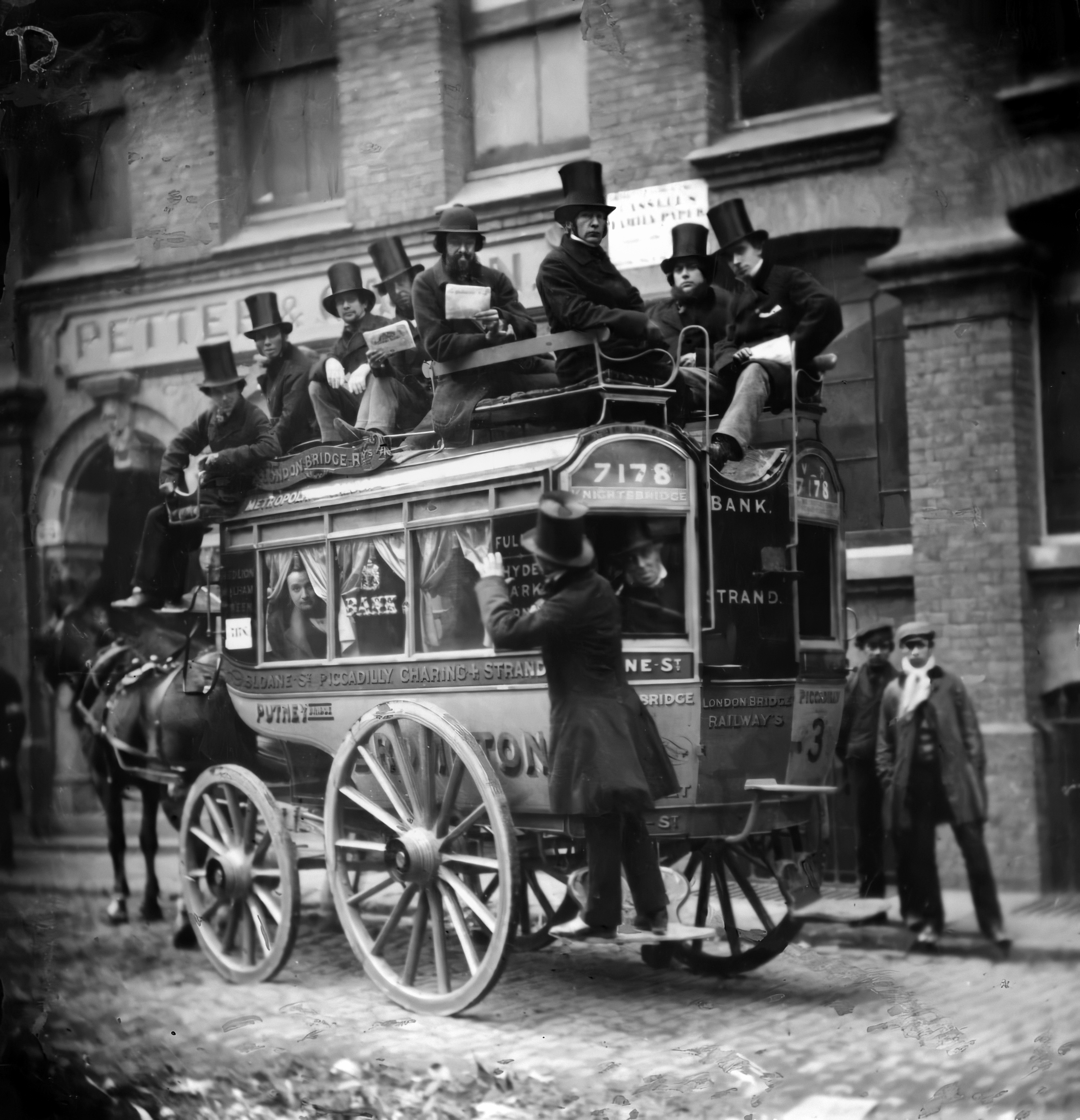

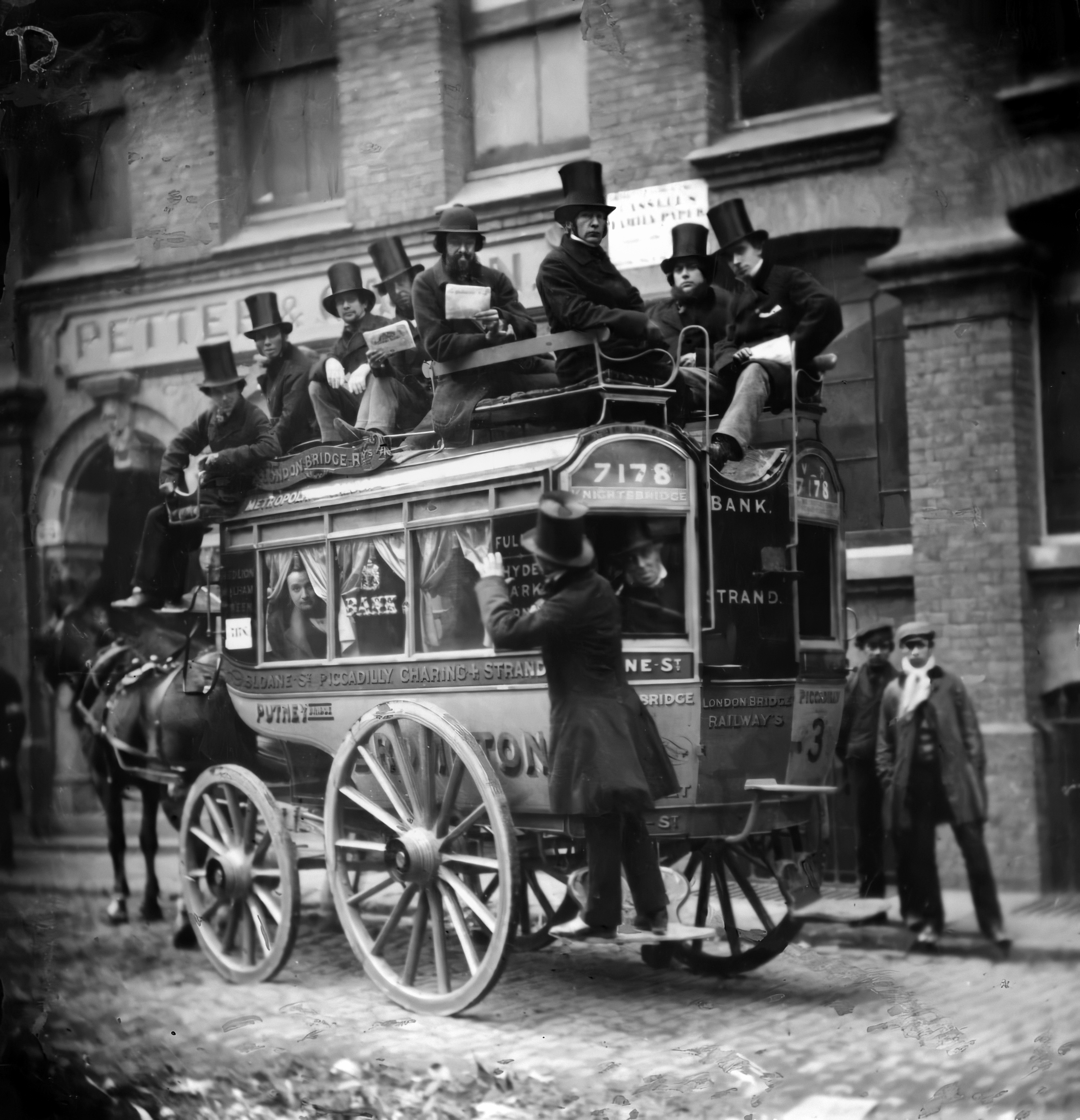

With the great railway terminals developing to connect London with its suburbs and beyond, mass transport was becoming ever more important within the city as its population increased. The first horse-drawn omnibuses entered service in London in 1829. By 1854 there were 3,000 of them in service, painted in bright reds, greens, and blues, and each carrying an average of 300 passengers per day. The two-wheeled

With the great railway terminals developing to connect London with its suburbs and beyond, mass transport was becoming ever more important within the city as its population increased. The first horse-drawn omnibuses entered service in London in 1829. By 1854 there were 3,000 of them in service, painted in bright reds, greens, and blues, and each carrying an average of 300 passengers per day. The two-wheeled  From the 1870s onwards, Londoners also had access to a developing tram network which accessed Central London and provided local transport in the suburbs. The first horse-drawn tramways were installed in 1860 along the

From the 1870s onwards, Londoners also had access to a developing tram network which accessed Central London and provided local transport in the suburbs. The first horse-drawn tramways were installed in 1860 along the

With traffic congestion on London's roads becoming more and more serious, proposals for underground railways to ease the pressure on street traffic were first mooted in the 1840s, after the opening of the Thames Tunnel in 1843 proved such engineering work could be done successfully. However, reservations over the stability of underground tunneling persisted into the 1860s and were finally overcome when Parliament approved the construction of London's first underground railway, the

With traffic congestion on London's roads becoming more and more serious, proposals for underground railways to ease the pressure on street traffic were first mooted in the 1840s, after the opening of the Thames Tunnel in 1843 proved such engineering work could be done successfully. However, reservations over the stability of underground tunneling persisted into the 1860s and were finally overcome when Parliament approved the construction of London's first underground railway, the

The impetus for this building was London's massive population growth, which put a constant strain on existing communications between the north and south banks. The want of overland bridges was one of the issues cited by the ''

The impetus for this building was London's massive population growth, which put a constant strain on existing communications between the north and south banks. The want of overland bridges was one of the issues cited by the ''

The development of

The development of

In addition to the museums, popular entertainment proliferated throughout the city. At the beginning of the century, there were only three theatres in operation in London: the "winter" theatres of the

In addition to the museums, popular entertainment proliferated throughout the city. At the beginning of the century, there were only three theatres in operation in London: the "winter" theatres of the

Many famous buildings and landmarks of London were constructed during the 19th century, including:

*Buckingham Palace

*Trafalgar Square

*Nelson's Column

*Clock Tower, Palace of Westminster, Big Ben and the Palace of Westminster, Houses of Parliament

*

Many famous buildings and landmarks of London were constructed during the 19th century, including:

*Buckingham Palace

*Trafalgar Square

*Nelson's Column

*Clock Tower, Palace of Westminster, Big Ben and the Palace of Westminster, Houses of Parliament

*

online free to borrow

* Richardson, John. ''The annals of London : a year-by-year record of a thousand years of history'' ( U of California Press, 2000

online free to borrow

* Gareth Stedman Jones, Stedman Jones, Gareth. ''Outcast London: a study in the relationship between classes in Victorian society'' (Verso Books, 2014). * Walkowitz, Judith R. ''City of dreadful delight: narratives of sexual danger in late-Victorian London'' (U of Chicago Press, 2013).

online free to borrow

* *Wells, Matthew. ''Modelling the Metropolis: The Architectural Model in Victorian London'' (Zurich: gta Verlag, 2023)

online access here

* Wohl, Anthony. ''The eternal slum: housing and social policy in Victorian London'' (Routledge, 2017).

Illustrations

* * * *

index

*

bibliography

* *

v.4

*

1839 ed.

* * * * * * * *

v.6

* * * *A Christmas Carol, London: Charles Dickens, 1843 * * * * * * * *

index

* * *

1879 ed.

*

Index

* * *

1879 ed.

* * * + (1878 ed.) * *

Victorian London

Late 19th century London then and now

An exploration of vagrancy and streetwalkers in late Victorian London

Dictionary of Victorian London

A resource for anyone interested in life in Victorian London. {{DEFAULTSORT:19th century London 19th century in London, 19th century-related lists

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

grew enormously to become a global city

A global city (also known as a power city, world city, alpha city, or world center) is a city that serves as a primary node in the global economic network. The concept originates from geography and urban studies, based on the thesis that glo ...

of immense importance. It was the largest city in the world from about 1825, the world's largest port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Hamburg, Manch ...

, and the heart of international finance

International finance (also referred to as international monetary economics or international macroeconomics) is the branch of monetary economics, monetary and macroeconomics, macroeconomic interrelations between two or more countries. Internation ...

and trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

Traders generally negotiate through a medium of cr ...

. Railways connecting London to the rest of Britain, as well as the London Underground

The London Underground (also known simply as the Underground or as the Tube) is a rapid transit system serving Greater London and some parts of the adjacent home counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and Hertfordshire in England.

The Undergro ...

, were built, as were roads, a modern sewer system and many famous sites.

Overview

During the 19th century, London was transformed into the world's largest city and capital of the

During the 19th century, London was transformed into the world's largest city and capital of the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

. The population rose from over 1 million in 1801 to 5.567 million in 1891. In 1897, the population of "Greater London

Greater London is an administrative area in England, coterminous with the London region, containing most of the continuous urban area of London. It contains 33 local government districts: the 32 London boroughs, which form a Ceremonial count ...

" (defined here as the Metropolitan Police District plus the City of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

) was estimated at 6.292 million. By the 1860s it was larger by one quarter than the world's second most populous city, Beijing, two-thirds larger than Paris, and five times larger than New York City.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the urban core of London was bounded to the west by Park Lane and Hyde Park, and by Marylebone Road to the north. It extended along the south bank of the Thames at Southwark

Southwark ( ) is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed ...

, and to the east as far as Bethnal Green

Bethnal Green is an area in London, England, and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in east London and part of the East End of London, East End. The area emerged from the small settlement which developed around the common la ...

and Spitalfields

Spitalfields () is an area in London, England and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in East London and situated in the East End of London, East End. Spitalfields is formed around Commercial Street, London, Commercial Stre ...

. At the beginning of the century, Hyde Park Corner was considered the western entrance to London; a turnpike gate was in operation there until 1825. With the population growing at an increasing rate, so too did the territory of London expand significantly: the city encompassed 122 square miles in 1851 and had grown to 693 square miles by 1896.

During this period, London became a global political, financial, and trading capital. While the city grew wealthy as Britain's holdings expanded, 19th-century London was also a city of poverty, where millions lived in overcrowded and unsanitary slum

A slum is a highly populated Urban area, urban residential area consisting of densely packed housing units of weak build quality and often associated with poverty. The infrastructure in slums is often deteriorated or incomplete, and they are p ...

s. Life for the poor was immortalized by Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

in such novels as '' Oliver Twist''.

One of the most famous events of 19th-century London was the Great Exhibition of 1851

Great may refer to:

Descriptions or measurements

* Great, a relative measurement in physical space, see Size

* Greatness, being divine, majestic, superior, majestic, or transcendent

People

* List of people known as "the Great"

* Artel Great (bo ...

. Held at The Crystal Palace

The Crystal Palace was a cast iron and plate glass structure, originally built in Hyde Park, London, to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The exhibition took place from 1 May to 15 October 1851, and more than 14,000 exhibitors from around ...

, the fair attracted visitors from across the world and displayed Britain at the height of its imperial dominance.

Immigrants

As the capital of a massive empire, London became a draw for immigrants from the colonies and poorer parts of Europe. A large Irish population settled in the city during theVictorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the reign of Queen Victoria, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. Slightly different definitions are sometimes used. The era followed the ...

, with many of the newcomers refugees from the Great Famine (1845–1849). At one point, Irish immigrants made up about 20% of London's population. In 1853 the number of Irish in London was estimated at 200,000, so large a population in itself that if it were a city it would have ranked as the third largest in England, and was about equal to the combined populations of Limerick

Limerick ( ; ) is a city in western Ireland, in County Limerick. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and is in the Mid-West Region, Ireland, Mid-West which comprises part of the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. W ...

, Belfast

Belfast (, , , ; from ) is the capital city and principal port of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan and connected to the open sea through Belfast Lough and the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North Channel ...

, and Cork.

London also became home to a sizable Jewish community, estimated to be around 46,000 in 1882, and a very small Indian population consisting largely of transitory sailors known as lascars. In the 1880s and 1890s tens of thousands of Jews escaping persecution and poverty in Eastern Europe came to London and settled largely in the East End around Houndsditch, Whitechapel

Whitechapel () is an area in London, England, and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in east London and part of the East End of London, East End. It is the location of Tower Hamlets Town Hall and therefore the borough tow ...

, Aldgate, and parts of Spitalfields

Spitalfields () is an area in London, England and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in East London and situated in the East End of London, East End. Spitalfields is formed around Commercial Street, London, Commercial Stre ...

.Glinert, 2012; p. 294 Many came to find work in the sweatshops and markets of the rag trade, refashioning and re-selling clothing, which itself was centered around Petticoat Lane Market and the "Rag Fair" in Houndsditch, London's largest second-hand clothing market. As members of the Jewish community prospered in the latter part of the century, many left the East End and settled in the immediate suburbs of Dalston, Hackney, Stoke Newington

Stoke Newington is an area in the northwest part of the London Borough of Hackney, England. The area is northeast of Charing Cross. The Manor of Stoke Newington gave its name to Stoke Newington (parish), Stoke Newington, the ancient parish. S ...

, Stamford Hill, and parts of Islington

Islington ( ) is an inner-city area of north London, England, within the wider London Borough of Islington. It is a mainly residential district of Inner London, extending from Islington's #Islington High Street, High Street to Highbury Fields ...

.

An Italian community coalesced in Soho

SoHo, short for "South of Houston Street, Houston Street", is a neighborhood in Lower Manhattan, New York City. Since the 1970s, the neighborhood has been the location of many artists' lofts and art galleries, art installations such as The Wall ...

and in Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell ( ) is an area of central London, England.

Clerkenwell was an Civil Parish#Ancient parishes, ancient parish from the medieval period onwards, and now forms the south-western part of the London Borough of Islington. The St James's C ...

, centered along Saffron Hill, Farringdon Road, Rosebery Avenue, and Clerkenwell Road

Clerkenwell Road is a street in London.

It runs west–east from Gray's Inn Road in the west, to Goswell Road in the east. Its continuation at either end is Theobald's Road and Old Street respectively.

Clerkenwell Road and Theobalds Road wer ...

. Out of the 11,500 Italians living in London in 1900, Soho accounted for 6,000, and Clerkenwell 4,000. Most of these were young men, engaged in occupations like organ grinding or selling street food (2,000 Italians were classed as "ice cream, salt, and walnut vendors" in 1900).

After the Strangers' Home for Asiatics, Africans and South Sea Islanders opened on West India Dock Road in 1856, a small population of Chinese sailors began to settle in Limehouse

Limehouse is a district in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in East London. It is east of Charing Cross, on the northern bank of the River Thames. Its proximity to the river has given it a strong maritime character, which it retains throu ...

, around Limehouse Causeway and Pennyfields. The 1881 census recorded that of the 22 people who lived there, eleven were born in China, six in India or Sri Lanka, two in Arabia, two in Singapore and one in the Kru Coast of Africa. These men married and opened shops and boarding houses which catered to the transient population of "Chinese firemen, seamen, stewards, cooks and carpenters who serve on board the steamers plying between Germany and the port of London". London's first Chinatown, as this area of Limehouse became known, was depicted in novels like Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

' '' The Mystery of Edwin Drood'' and Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Fflahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish author, poet, and playwright. After writing in different literary styles throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular and influential playwright ...

's ''The Picture of Dorian Gray

''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' is an 1890 philosophical fiction and Gothic fiction, Gothic horror fiction, horror novel by Irish writer Oscar Wilde. A shorter novella-length version was published in the July 1890 issue of the American period ...

'' as a sinister quarter of crime and opium dens. Racist stereotypes of the Chinese which abounded in the 19th and early 20th centuries exaggerated both the criminality and the population of Chinatown.

Economy

Port of London

London was both the world's largest port, and a major shipbuilding centre in itself, for the entire 19th century. At the beginning of the century, this role was far from secure after the strong growth in world commerce during the later decades of the 18th century rendered the overcrowded Pool of London incapable of handling shipping levels efficiently. Sailors could wait a week or more to offload their cargoes, which left the ships vulnerable to theft and enabled widespread evasion of import duties. Losses on imports alone from theft were estimated at £500,000 per year in the 1790s – estimates for the losses on exports have never been made. Anxious West Indian traders combined to fund a private police force to patrol Thames shipping in 1798, under the direction of magistrate Patrick Colquhoun and Master Mariner John Harriott.Dick Paterson, Origins of the Thames Police (Thames Police Museum)accessed 15 September 2020 This Marine Police Force, regarded as the first modern police force in England, was a success at apprehending would-be thieves, and it was made a public force via the Depredations on the Thames Act 1800.Marine Police History

accessed 15 September 2020 In 1839 the force would be absorbed into and become the Thames Division of the Metropolitan Police. In addition to theft, at the turn of the century commercial interests feared the competition from rising English ports like

Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

and Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

. This spurred Parliament in 1799 to pass the Port of London Improvement and City Canal Act 1799 ( 39 Geo. 3. c. lxix) to authorize the first major dock construction work of the 19th century, the West India Docks

The West India Docks are a series of three docks, quaysides, and warehouses built to import goods from, and export goods and occasionally passengers to, the British West Indies. Located on the Isle of Dogs in London, the first dock opened in 18 ...

, on the Isle of Dogs. Situated east of London Bridge, shipping could avoid the dangerous and congested upper reaches of the Thames. The three West India Docks were self-contained and accessed from the river via a system of locks and basins, offering an unprecedented level of security. The new warehouses surrounding the docks could accommodate close to a million tons of storage, with the Import and Export basins able to moor almost 400 ships at a time.

The Commercial Road was built in 1803 as a conduit for newly arrived goods from the Isle of Dogs straight into the City of London, and the Grand Junction Canal Act 1812 ( 52 Geo. 3. c. cxl) provided for the docks to be integrated into the national canal system via the extension of the Grand Union Canal

The Grand Union Canal in England is part of the Canals of the United Kingdom, British canal system. It is the principal navigable waterway between London and the Midlands. Starting in London, one arm runs to Leicester and another to Birmi ...

to Limehouse

Limehouse is a district in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in East London. It is east of Charing Cross, on the northern bank of the River Thames. Its proximity to the river has given it a strong maritime character, which it retains throu ...

. The Regent's Canal, as this new branch between Paddington

Paddington is an area in the City of Westminster, in central London, England. A medieval parish then a metropolitan borough of the County of London, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965. Paddington station, designed b ...

and Limehouse became known, was the only canal link to the Thames, connecting a vital shipping outlet with the great industrial cities of The Midlands

The Midlands is the central region of England, to the south of Northern England, to the north of southern England, to the east of Wales, and to the west of the North Sea. The Midlands comprises the ceremonial counties of Derbyshire, Herefords ...

. The Regent's Canal became a huge success, but on a local rather than a national level because it facilitated the localized transport of goods like coal, timber, and other building materials around London. Easy access to coal shipments from northeast England via the Port of London meant that a profusion of industries proliferated along the Regent's Canal, especially gasworks, and later electricity plants.

Within a few years, the West India Docks were joined by the smaller East India Docks just northeast in Blackwall, as well as the London Docks

The London Docks were one of several sets of docks in the historic Port of London.

They were constructed in Wapping, downstream from the City of London between 1799 and 1815, at a cost exceeding £5½ million.

Traditionally ships had d ...

in Wapping

Wapping () is an area in the borough of Tower Hamlets in London, England. It is in East London and part of the East End. Wapping is on the north bank of the River Thames between Tower Bridge to the west, and Shadwell to the east. This posit ...

. The St Katharine Docks

St Katharine Docks is a former dock in the St Katherine and Wapping ward of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It lies in the East End of London, East End on the north bank of the River Thames, immediately downstream of the Tower of London an ...

built just east of the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

were completed in 1828, and later joined with the London Docks (in 1869). In Rotherhithe

Rotherhithe ( ) is a district of South London, England, and part of the London Borough of Southwark. It is on a peninsula on the south bank of the Thames, facing Wapping, Shadwell and Limehouse on the north bank, with the Isle of Dogs to the ea ...

, where the Greenland Dock was operating at the beginning of the century, new docks, ponds and the Grand Surrey Canal were added in the early 19th century by several small companies. The area became known for specializing in commerce from the Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

*Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originatin ...

, Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

, and North America, especially for its large timber ponds and grain imports from North America. In 1864 the various companies amalgamated to form the Surrey Commercial Docks Company, which by 1878 constituted 13 docks and ponds.

With the eclipse of the sailing ship by the

With the eclipse of the sailing ship by the steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

in mid-century, tonnages grew larger and the shallow docks nearer the city were too small for mooring them. In response, new commercial docks were built beyond the Isle of Dogs: the Royal Victoria Dock

The Royal Victoria Dock is the largest of three docks in the Royal Docks of east London, now part of the redeveloped London Docklands, Docklands.

History

Although, the structure was in place in the year 1850, it was opened in 1855, on a pre ...

(1855), the Millwall Dock (1868), the Royal Albert Dock (1880), and finally, the Port of Tilbury

The Port of Tilbury is a port located on the River Thames at Tilbury in Essex, England. It serves as the principal port for London, as well as being the main United Kingdom port for handling the importation of paper. There are extensive facili ...

(1886), 26 miles east of London Bridge. The Victoria was unprecedented in size: 1.5 miles in total length, encompassing over 100 acres. Hydraulic

Hydraulics () is a technology and applied science using engineering, chemistry, and other sciences involving the mechanical properties and use of liquids. At a very basic level, hydraulics is the liquid counterpart of pneumatics, which concer ...

locks and purpose-built railway connections to the national transport network made the Victoria as technologically advanced as it was large. It was a great commercial success, but within two decades it was becoming too shallow, and the lock entrance too narrow, for newer ships. The St. Katharine and London Dock Company built the Royal Albert Dock adjoining the Victoria; this new quay was 1.75 miles long, with 16,500 feet of deep water quayage. It was the largest dock in the world, the first to be electrically lit, featured hydraulically operated cranes, and like its sister the Victoria, was connected to the national railways. This feverish building obtained clear results: by 1880, the Port of London was receiving 8 million tons of goods a year, a 10-fold increase over the 800,000 being received in 1800.

Shipping in the Port of London supported a vast army of transport and warehouse workers, who characteristically attended the "call-on" each morning at the entrances to the docks to be assigned work for the day. This type of work was low-paid and highly unstable, drying up depending on the season and the vagaries of world trade. The poverty of the dock workers and growing trade union activism coalesced into the Great Strike of 1889, when an estimated 130,000 workers went on strike between 14 August and 16 September. The strike paralysed the port and led the dock owners to concede all of the demands of the strike committee, including a number of fairer working arrangements, the reduction of the "call-on", and higher hourly and overtime wages.

Shipbuilding

During the first half of the 19th century, the shipbuilding industry on the Thames was highly innovative and produced some of the most technologically advanced vessels in the world. The firm of Wigram and Green constructed Blackwall frigates from the early 1830s, a faster version of theEast Indiaman

East Indiamen were merchant ships that operated under charter or licence for European trading companies which traded with the East Indies between the 17th and 19th centuries. The term was commonly used to refer to vessels belonging to the Bri ...

sailing ship, while the naval engineer John Scott Russell

John Scott Russell (9 May 1808, Parkhead, Glasgow – 8 June 1882, Ventnor, Isle of Wight) was a Scottish civil engineer, naval architecture, naval architect and shipbuilder who built ''SS Great Eastern, Great Eastern'' in collaboration with Is ...

designed more refined hulls for the ships constructed in his Millwall Iron Works. London shipyards had supplied about 60% of the Admiralty's warships in service in 1866. The largest shipbuilder on the Thames, the Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company

The Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company, Limited was a shipyard and iron works straddling the mouth of Bow Creek at its confluence with the River Thames, at Leamouth Wharf (often referred to as Blackwall) on the west side and at Cann ...

, produced the revolutionary broadside ironclad '' HMS Warrior'' (1860), the largest warship in the world and the first iron-hulled, armor plated vessel, alongside its sister '' HMS Black Prince'' (1861). Over the next few years, five out of the nine armored ironclads commissioned by the Navy to follow the example of the ''Warrior'' would be constructed in London. The Thames Ironworks was employed not just in shipbuilding, but in civil engineering works around London like Blackfriars Railway Bridge, Hammersmith Bridge, and the construction of the iron-girded roofs of Alexandra Palace

Alexandra Palace is an entertainment and sports venue in North London, situated between Wood Green and Muswell Hill in the London Borough of Haringey. A listed building, Grade II listed building, it is built on the site of Tottenham Wood and th ...

and the 1862 International Exhibition

The International Exhibition of 1862, officially the London International Exhibition of Industry and Art, also known as the Great London Exposition, was a world's fair held from 1 May to 1 November 1862 in South Kensington, London, England. Th ...

building.

London engineering firms like Maudslay, Sons and Field

Maudslay, Sons and Field was an engineering company based in Lambeth

Lambeth () is a district in South London, England, which today also gives its name to the (much larger) London Borough of Lambeth. Lambeth itself was an ancient parish in ...

and John Penn and Sons were early developers and suppliers of marine steam engines for merchant and naval ships, fueling the transition from sail to steam powered locomotion. This was aided by the 1834 invention by Samuel Hall of Bow of a condenser for cooling boilers which used fresh water rather than corrosive salt water. In 1838 the first screw-propelled steamer in the world, '' SS Archimedes'', was launched at Ratcliff Cross Dock, an alternative to the less efficient paddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine driving paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, whereby the first uses were wh ...

. By 1845 the Admiralty had settled upon screw propellers as the optimal form of propulsion, and a slew of new battleships were built in London dockyards equipped with the new technology. The largest and most famous ship of its day, the '' SS Great Eastern'', a collaboration between John Scott Russell and Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel ( ; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was an English civil engineer and mechanical engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history", "one of the 19th-century engi ...

, was constructed at the Millwall Iron Works and launched in 1858. It still holds the record as the largest ship to have been launched on the Thames, and held the record as the largest ship in the world by tonnage until 1901.

Despite the astonishing successes of the shipbuilding industry in the first half of the century, in the last decades of the 19th century the industry experienced a precipitous decline that would leave only one large firm, the Thames Ironworks, in existence by the mid-1890s. London shipyards lacked the capacity, and the ability to expand, for building the large vessels in demand by the later 19th century, losing business to newer shipyards in Scotland and the North of England, where labor and overhead costs were lower, and iron and coal deposits much closer. The ancient Royal Dockyards at Woolwich

Woolwich () is a town in South London, southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich.

The district's location on the River Thames led to its status as an important naval, military and industrial area; a role that was mainta ...

and Deptford

Deptford is an area on the south bank of the River Thames in southeast London, in the Royal Borough of Greenwich and London Borough of Lewisham. It is named after a Ford (crossing), ford of the River Ravensbourne. From the mid 16th century ...

, founded by Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

in the 16th century, were too far upriver and too shallow due to the silting up of the Thames, forcing their closure in 1869.

Finance

TheCity of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

's importance as a financial centre increased substantially over the course of the 19th century. The city's strengths in banking, stock brokerage, and shipping insurance made it the natural channel for the huge rise in capital investment which occurred after the end of the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

in 1815. The city was also the headquarters of most of Britain's shipping firms, trading houses, exchanges and commercial firms like railway companies and import houses. As the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

gathered pace, an insatiable demand for capital investment in railways, shipping, industry and agriculture fueled the growth of financial services in the city. The end of the Napoleonic Wars also freed up British capital to flow overseas; there was some £100 million invested abroad between 1815 and 1830, and as much as £550 million by 1854. At the end of the century, the net total of British foreign investment stood at £2.394 billion. The 1862 '' Bradshaw's Guide'' to London listed 83 banks, 336 stockbroking firms, 37 currency brokers, 248 ship and insurance brokerages, and 1500 different merchants in the city, selling wares of every conceivable variety. At the centre of this nexus of private capital and commerce lay the Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the Kingdom of England, English Government's banker and debt manager, and still one ...

, which by the end of the century contained £20 million worth of gold reserves. It employed over 900 people and printed 15,000 new banknotes each day by 1896, doing some £2 million worth of business each day.

The result of the shift to financial services in the city was that, even while its residential population was ebbing in favor of the suburbs (there was a net loss of 100,000 people between 1840 and 1900), it retained its historical role as the center of English commerce. The working population swelled from some 200,000 in 1871 to 364,000 by 1911.

Housing

London's great expansion in the 19th century was driven by housing growth to accommodate the rapidly expanding population of the city. The growth of transport in London in this period fueled the outward expansion of suburbs, as did a cultural impetus to escape the inner city, allowing the worlds of 'work' and 'life' to be separate. Suburbs varied enormously in character and in the relative wealth of their inhabitants, with some being for the very wealthy, and others being for the lower-middle classes. They frequently imitated the success of earlier periods of speculative housing development from theGeorgian era

The Georgian era was a period in British history from 1714 to , named after the House of Hanover, Hanoverian kings George I of Great Britain, George I, George II of Great Britain, George II, George III and George IV. The definition of the Geor ...

, although the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the reign of Queen Victoria, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. Slightly different definitions are sometimes used. The era followed the ...

saw a much wider array of suburban housing built in London. Terraced, semi-detached

A semi-detached house (often abbreviated to semi) is a single-family Duplex (building), duplex dwelling that shares one common party wall, wall with its neighbour. The name distinguishes this style of construction from detached houses, with no sh ...

and detached

A single-family detached home, also called a single-detached dwelling, single-family residence (SFR) or separate house is a free-standing residential building. It is defined in opposition to a multi-family residential dwelling.

Definitions ...

housing all developed in a multitude of styles and typologies, with an almost endless variation in the layout of streets, gardens, homes, and decorative elements.

Suburbs were aspirational for many, but also came to be lampooned and satirised in the press for the conservative and conventional tastes they represented (for example in '' Punch's'' Pooter). While the Georgian terrace has been described as "England's greatest contribution to the urban form", the increasing rigour with which Building Act regulations were applied after 1774 led to increasingly simple, standardised designs, which by the end of the 19th century were accommodating many households at the lower end of the socio-economic scale. Indeed, more grandly designed examples became less common by this period, as the very wealthy tended to prefer detached homes, and terraces in particular now became associated first with the aspirational middle classes, and later with the lower middle classes in more industrial areas of London such as the East End.

While many areas of Georgian and Victorian suburbs were damaged heavily in

Suburbs were aspirational for many, but also came to be lampooned and satirised in the press for the conservative and conventional tastes they represented (for example in '' Punch's'' Pooter). While the Georgian terrace has been described as "England's greatest contribution to the urban form", the increasing rigour with which Building Act regulations were applied after 1774 led to increasingly simple, standardised designs, which by the end of the 19th century were accommodating many households at the lower end of the socio-economic scale. Indeed, more grandly designed examples became less common by this period, as the very wealthy tended to prefer detached homes, and terraces in particular now became associated first with the aspirational middle classes, and later with the lower middle classes in more industrial areas of London such as the East End.

While many areas of Georgian and Victorian suburbs were damaged heavily in The Blitz

The Blitz (English: "flash") was a Nazi Germany, German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom, for eight months, from 7 September 1940 to 11 May 1941, during the Second World War.

Towards the end of the Battle of Britain in 1940, a co ...

and/or then redeveloped through slum clearance

Slum clearance, slum eviction or slum removal is an urban renewal strategy used to transform low-income settlements with poor reputation into another type of development or housing. This has long been a strategy for redeveloping urban communities; ...

, much of Inner London

Inner London is the group of London boroughs that form the interior part of Greater London and are surrounded by Outer London. With its origins in the bills of mortality, it became fixed as an area for statistics in 1847 and was used as an area ...

's character remains dominated by the suburbs built successively during Georgian and Victorian times, and such houses remain enormously popular.

Living conditions

Poverty

In contrast to the conspicuous wealth of the cities of London and Westminster, there was a huge underclass of desperately poor Londoners within a short range of the more affluent areas. The author George W. M. Reynolds commented on the vast wealth disparities and misery of London's poorest in 1844: In Central London, the single most notorious slum was St. Giles, a name which by the 19th century had passed into common parlance as a byword for extreme poverty. Infamous since the mid 18th century, St. Giles was defined by its prostitutes, gin shops, secret alleyways where criminals could hide, and horribly overcrowded tenements.Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824) was an English poet. He is one of the major figures of the Romantic movement, and is regarded as being among the greatest poets of the United Kingdom. Among his best-kno ...

excoriated the state of St. Giles in a speech to the House of Lords in 1812, stating that "I have been in some of the most oppressed provinces of Turkey, but never under the most despotic of infidel governments did I behold such squalid wretchedness as I have seen since my return in the very heart of a Christian country." At the heart of this area, now occupied by New Oxford Street and Centre Point, was "The Rookery", a particularly dense warren of houses along George Street and Church Lane, the latter of which in 1852 was reckoned to contain over 1,100 lodgers in overpacked, squalid buildings with open sewers. The poverty worsened with the massive influx of poor Irish immigrants during the Great Famine of 1848, giving the area the name "Little Ireland", or "The Holy Land". Government intervention beginning in the 1830s reduced the area of St. Giles through mass evictions, demolitions, and public works projects. New Oxford Street was built right through the heart of "The Rookery" in 1847, eliminating the worst part of the area, but many of the evicted inhabitants simply moved to neighboring streets, which remained stubbornly mired in poverty.

Mass demolition of slums like St. Giles was the usual method of removing problematic pockets of the city; for the most part this just displaced existing residents because the new dwellings built by private developers were often far too expensive for the previous inhabitants to afford. In the mid to late 19th century, philanthropists like Octavia Hill

Octavia Hill (3December 183813August 1912) was an English Reform movement, social reformer and founder of the National Trust. Her main concern was the welfare of the inhabitants of cities, especially London, in the second half of the nineteent ...

and charities like the Peabody Trust

The Peabody Trust was founded in 1862 as the Peabody Donation Fund and now brands itself simply as Peabody.

focused on building adequate housing for the working classes at affordable rates: George Peabody built his first improved housing for the "artisans and laboring poor" on Commercial Street in 1864. The Metropolitan Board of Works (the dominant authority before the LCC), was empowered to undertake clearances and to enforce overcrowding and other such standards on landlords by a stream of legislation including the Labouring Classes Dwelling Houses Act 1866 ( 29 & 30 Vict. c. 28) and the Labouring Classes Dwelling Houses Act 1867 ( 30 & 31 Vict. c. 28). Overcrowding was also defined as a public health 'nuisance' beginning in 1855, which allowed Medical Officers to report landlords in violation to the Board of Health. The shortcomings of the existing legislation were refined and condensed into one comprehensive piece of legislation, the Housing of the Working Classes Act 1890 ( 63 & 64 Vict. c. 59). This empowered the LCC to construct its own housing on cleared land, which it had been prohibited from doing before; thus began a social housing

Public housing, also known as social housing, refers to Subsidized housing, subsidized or affordable housing provided in buildings that are usually owned and managed by local government, central government, nonprofit organizations or a ...

building program in targeted areas like Bethnal Green

Bethnal Green is an area in London, England, and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in east London and part of the East End of London, East End. The area emerged from the small settlement which developed around the common la ...

and Millbank

Millbank is an area of central London in the City of Westminster. Millbank is located by the River Thames, east of Pimlico and south of Westminster. Millbank is known as the location of major government offices, Burberry headquarters, the Mill ...

that would accelerate in the next century.

The East End

The East End of London, with an economy oriented around the Docklands and the polluting industries clustered along the Thames and the

The East End of London, with an economy oriented around the Docklands and the polluting industries clustered along the Thames and the River Lea

The River Lea ( ) is in the East of England and Greater London. It originates in Bedfordshire, in the Chiltern Hills, and flows southeast through Hertfordshire, along the Essex border and into Greater London, to meet the River Thames at Bow Cr ...

, had long been an area of working poor. By the late 19th century it was developing an increasingly sinister reputation for crime, overcrowding, desperate poverty, and debauchery. The 1881 census counted over 1 million inhabitants in the East End, a third of whom lived in poverty. The Cheap Trains Act 1883 ( 46 & 47 Vict. c. 34), while it enabled many working class Londoners to move away from the inner city, also accentuated the poverty in areas like the East End, where the most destitute were left behind. Prostitution was rife, with one official report in 1888 recording 62 brothels and 1,200 prostitutes in Whitechapel

Whitechapel () is an area in London, England, and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in east London and part of the East End of London, East End. It is the location of Tower Hamlets Town Hall and therefore the borough tow ...

(the real number was likely much higher).

The American author Jack London

John Griffith London (; January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as Jack London, was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors t ...

, in his 1903 account ''The People of the Abyss

''The People of the Abyss'' is a 1903 book by Jack London, containing his first-hand account of several weeks spent living in the Whitechapel district of the East End of London in 1902. London attempted to understand the working-class of this ...

'', described the bewilderment of Londoners when he mentioned that he planned to visit the East End: many of them had never been there despite living in the same city. He was refused a guide when he visited the travel agency of Thomas Cook & Son

Thomas Cook & Son, originally simply Thomas Cook, was a British travel company that existed from 1841 to 2001. It arranged transport, tours and holidays worldwide. It was owned by the British government from 1948 to 1972.

The company was foun ...

, which told him to consult the police. When he finally found a reluctant cabbie to take him into Stepney

Stepney is an area in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in the East End of London. Stepney is no longer officially defined, and is usually used to refer to a relatively small area. However, for much of its history the place name was applied to ...

, he described his impression as follows:

By the time of Jack London's visit in 1903, the reputation of the East End was at its lowest ebb after decades of unfavourable attention from journalists, authors, and social reformers. The 1888 Whitechapel murders

The Whitechapel murders were committed in or near the impoverished Whitechapel District (Metropolis), Whitechapel district in the East End of London between 3 April 1888 and 13 February 1891. At various points some or all of these eleven unso ...

perpetrated by Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer who was active in and around the impoverished Whitechapel district of London, England, in 1888. In both criminal case files and the contemporaneous journalistic accounts, the killer was also ...

brought international attention to the squalor and criminality of the East End, while penny dreadfuls and a slew of sensational novels like George Gissing

George Robert Gissing ( ; 22 November 1857 – 28 December 1903) was an English novelist, who published 23 novels between 1880 and 1903. In the 1890s he was considered one of the three greatest novelists in England, and by the 1940s he had been ...

's '' The Nether World'' and the works of Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

painted grim pictures of London's deprived areas for middle and upper class readers. The single most influential work on London poverty was Charles Booth's ''Life and Labour of the People in London

''Life and Labour of the People in London'' was a multi-volume book by Charles Booth (social reformer), Charles Booth which provided a survey of the lives and occupations of the working class of late 19th-century London, 19th century London. Th ...

'', a 17-volume work published between 1889 and 1903. Booth painstakingly charted levels of deprivation throughout the city, painting a bleak but also sympathetic picture of the wide variety of conditions experienced by London's poor.

Disease and mortality

The extreme population density in areas like the East End made for unsanitary conditions and resulting epidemics of disease. The child mortality rate in the East End stood at 20%, while the estimated life expectancy of an East End labourer was only 19 years. InBethnal Green

Bethnal Green is an area in London, England, and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in east London and part of the East End of London, East End. The area emerged from the small settlement which developed around the common la ...

, one of London's poorest districts, the mortality rate stood at 1 in 41 in 1847. The average for Bethnal Green between the years 1885 and 1893 remained virtually the same as that of 1847. Meanwhile, the mortality average for those same eight years in the wealthy boroughs of Kensington

Kensington is an area of London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, around west of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up by Kensingt ...

and Paddington

Paddington is an area in the City of Westminster, in central London, England. A medieval parish then a metropolitan borough of the County of London, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965. Paddington station, designed b ...

stood at roughly 1 in 53. London's overall mortality rate was tracked at a ratio of roughly 1 in 43 between the years 1869–1879; overall life expectancy in the city stood at just 37 years in midcentury.

The most serious disease in the poor quarters was tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

, until the 1860s cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

, as well as rickets

Rickets, scientific nomenclature: rachitis (from Greek , meaning 'in or of the spine'), is a condition that results in weak or soft bones in children and may have either dietary deficiency or genetic causes. Symptoms include bowed legs, stun ...

, scarlet fever

Scarlet fever, also known as scarlatina, is an infectious disease caused by ''Streptococcus pyogenes'', a Group A streptococcus (GAS). It most commonly affects children between five and 15 years of age. The signs and symptoms include a sore ...

, and typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by ''Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often ther ...

. Between 1850 and 1860 the mortality rate from typhoid was 116 per 100,000 people. Smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

was a dreaded disease across London: there were epidemics in 1816–19, 1825–26, 1837–40, 1871 and 1881. A speckling of workhouse

In Britain and Ireland, a workhouse (, lit. "poor-house") was a total institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. In Scotland, they were usually known as Scottish poorhouse, poorh ...

hospitals and the London Smallpox Hospital in St Pancras (moved to Highgate

Highgate is a suburban area of N postcode area, north London in the London Borough of Camden, London Boroughs of Camden, London Borough of Islington, Islington and London Borough of Haringey, Haringey. The area is at the north-eastern corner ...

Hill in 1848–50), were all that existed to treat smallpox victims until the latter part of the century. This changed with the creation of the Metropolitan Asylums Board in 1867, which embarked on the building of five planned smallpox and fever hospitals in Stockwell, Deptford

Deptford is an area on the south bank of the River Thames in southeast London, in the Royal Borough of Greenwich and London Borough of Lewisham. It is named after a Ford (crossing), ford of the River Ravensbourne. From the mid 16th century ...

, Hampstead

Hampstead () is an area in London, England, which lies northwest of Charing Cross, located mainly in the London Borough of Camden, with a small part in the London Borough of Barnet. It borders Highgate and Golders Green to the north, Belsiz ...

, Fulham

Fulham () is an area of the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham in West London, England, southwest of Charing Cross. It lies in a loop on the north bank of the River Thames, bordering Hammersmith, Kensington and Chelsea, London, Chelsea ...

and Homerton

Homerton ( ) is an area in London, England, in the London Borough of Hackney. It is bordered to the west by Hackney Central, to the north by Lower Clapton, in the east by Hackney Wick, Leyton and by South Hackney to the south. In 2019, it had ...

to serve the different regions of London. Fearful residents succeeded in blocking the building of the Hampstead hospital, and residents in Fulham obtained an injunction preventing all but local cases of smallpox from being treated in their hospital. Thus, with only three hospitals in operation when the epidemic of 1881 began, the MAB was overwhelmed. and were leased as hospital ship

A hospital ship is a ship designated for primary function as a floating healthcare, medical treatment facility or hospital. Most are operated by the military forces (mostly navy, navies) of various countries, as they are intended to be used in or ...

s and entered service in July 1881, moored at Greenwich

Greenwich ( , , ) is an List of areas of London, area in south-east London, England, within the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Greater London, east-south-east of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime hi ...

. The following year the two ships were purchased along with another, ''Castalia'', and the fleet was moved to Long Reach at Gravesend

Gravesend is a town in northwest Kent, England, situated 21 miles (35 km) east-southeast of Charing Cross (central London) on the Bank (geography), south bank of the River Thames, opposite Tilbury in Essex. Located in the diocese of Roche ...

, where it served 20,000 patients between 1884 and 1902. The floating hospitals were equipped with their own river ferry service to transport patients in isolation from the inner city. The ships enabled three permanent isolation hospitals to be built at Dartford

Dartford is the principal town in the Borough of Dartford, Kent, England. It is located south-east of Central London and

is situated adjacent to the London Borough of Bexley to its west. To its north, across the Thames Estuary, is Thurrock in ...

, effectively ending the threat of smallpox epidemics.

Transport

With the great railway terminals developing to connect London with its suburbs and beyond, mass transport was becoming ever more important within the city as its population increased. The first horse-drawn omnibuses entered service in London in 1829. By 1854 there were 3,000 of them in service, painted in bright reds, greens, and blues, and each carrying an average of 300 passengers per day. The two-wheeled

With the great railway terminals developing to connect London with its suburbs and beyond, mass transport was becoming ever more important within the city as its population increased. The first horse-drawn omnibuses entered service in London in 1829. By 1854 there were 3,000 of them in service, painted in bright reds, greens, and blues, and each carrying an average of 300 passengers per day. The two-wheeled hansom cab

The hansom cab is a kind of horse-drawn carriage designed and patented in 1834 by Joseph Hansom, an architect from York. The vehicle was developed and tested by Hansom in Hinckley, Leicestershire, England. Originally called the Hansom safet ...

, first seen in 1834, was the most common type of cab on London's roads throughout the Victorian era, but there were many types, like the four-wheeled Hackney carriage

A hackney or hackney carriage (also called a cab, black cab, hack or taxi) is a carriage or car for hire. A hackney of a more expensive or high class was called a remise. A symbol of London and Britain, the black taxi is a common sight on t ...

, in addition to the coaches, private carriages, coal-wagons, and tradesmen's vehicles which crowded the roads. There were 3,593 licensed cabs in London in 1852; by the end of the century there were estimated to be some 10,000 in all.

From the 1870s onwards, Londoners also had access to a developing tram network which accessed Central London and provided local transport in the suburbs. The first horse-drawn tramways were installed in 1860 along the

From the 1870s onwards, Londoners also had access to a developing tram network which accessed Central London and provided local transport in the suburbs. The first horse-drawn tramways were installed in 1860 along the Bayswater Road

Bayswater Road is the main road running along the northern edge of Hyde Park, London, Hyde Park in London. Originally part of the A40 road in London, A40 road, it is now designated part of the A402 road.

Route

In the east, Bayswater Road ...

at the northern edge of Hyde Park, Victoria Street in Westminster, and Kennington

Kennington is a district in south London, England. It is mainly within the London Borough of Lambeth, running along the boundary with the London Borough of Southwark, a boundary which can be discerned from the early medieval period between th ...

Street in South London. The trams were a success with passengers, but the raised rails were jolting and inconvenient for horse-drawn vehicles to cross, causing traffic bottlenecks at crossroads. Within a year the outcry was so great that the lines were pulled up, and trams were not reintroduced until the Tramways Act 1870 ( 33 & 34 Vict. c. 78) permitted them to be built again. Trams were restricted to operating in the suburbs of London, but they accessed the major transport hubs of the City and the West End, conveying passengers into and away from the suburbs. By 1893 there were about 1,000 tram cars across 135 miles worth of track. Trams could be accessed in Central London from Aldgate, Blackfriars Bridge, Borough

A borough is an administrative division in various English language, English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

...

, Moorgate, King's Cross, Euston Road

Euston Road is a road in Central London that runs from Marylebone Road to Kings Cross, London, King's Cross. The route is part of the London Inner Ring Road and forms part of the London congestion charge zone boundary. It is named after Euston ...

, Holborn

Holborn ( or ), an area in central London, covers the south-eastern part of the London Borough of Camden and a part (St Andrew Holborn (parish), St Andrew Holborn Below the Bars) of the Wards of the City of London, Ward of Farringdon Without i ...

, Shepherd's Bush

Shepherd's Bush is a suburb of West London, England, within the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham west of Charing Cross, and identified as a major metropolitan centre in the London Plan.

Although primarily residential in character, its ...

, Victoria, and Westminster Bridge

Westminster Bridge is a road-and-foot-traffic bridge crossing over the River Thames in London, linking Westminster on the west side and Lambeth on the east side.

The bridge is painted predominantly green, the same colour as the leather seats ...

.

Coming of the railways

19th-century London was transformed by the coming of the railways. A new network of metropolitan railways allowed the development of suburbs in neighboring counties from which middle-class and wealthy people could commute to the centre. While this spurred the massive outward growth of the city, London's growth also exacerbated the class divide, as the wealthier classes emigrated to the suburbs, leaving the poor to inhabit the inner city areas. The new railway lines were generally built through working class areas, where land was cheaper and compensation costs lower. In the 1860s, the railway companies were required to rehouse the tenants they evicted for construction, but these rules were widely evaded until the 1880s. The displaced generally stayed in the same area as before, but under more crowded conditions due to the loss of housing. The first railway to be built in London was the London and Greenwich Railway, a short line fromLondon Bridge

The name "London Bridge" refers to several historic crossings that have spanned the River Thames between the City of London and Southwark in central London since Roman Britain, Roman times. The current crossing, which opened to traffic in 197 ...

to Greenwich

Greenwich ( , , ) is an List of areas of London, area in south-east London, England, within the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Greater London, east-south-east of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime hi ...

, which opened in 1836. This was soon followed by great rail termini which linked London to every corner of Britain. These included Euston (1837), Paddington

Paddington is an area in the City of Westminster, in central London, England. A medieval parish then a metropolitan borough of the County of London, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965. Paddington station, designed b ...

(1838), Fenchurch Street

Fenchurch Street is a street in London, England, linking Aldgate at its eastern end with Lombard Street and Gracechurch Street in the west. It is a well-known thoroughfare in the City of London financial district and is the site of many cor ...

(1841), Waterloo (1848), King's Cross (1852), and St Pancras (1868). By 1865 there were 12 principal railway termini; the stations built along the lines in exurb

An exurb (or alternately: exurban area) is an area outside the typically denser inner suburbs, suburban area, at the edge of a metropolitan area, which has some economic and commuting connection to the metro area, low housing-density,

and rela ...

an villages surrounding London allowed commuter towns to be developed for the middle classes. The Cheap Trains Act 1883 helped poorer Londoners to relocate, by guaranteeing cheap fares and removing a duty

A duty (from "due" meaning "that which is owing"; , past participle of ; , whence "debt") is a commitment or expectation to perform some action in general or if certain circumstances arise. A duty may arise from a system of ethics or morality, e ...

imposed on fares since 1844. The new working class suburbs created as a result included West Ham

West Ham is a district in East London, England and is in the London Borough of Newham. It is an inner-city suburb located east of Charing Cross.

The area was originally an ancient parish formed to serve parts of the older Manor of Ham, a ...

, Walthamstow

Walthamstow ( or ) is a town within the London Borough of Waltham Forest in east London. The town borders Chingford to the north, Snaresbrook and South Woodford to the east, Leyton and Leytonstone to the south, and Tottenham to the west. At ...

, Kilburn, and Willesden

Willesden () is an area of north-west London, situated 5 miles (8 km) north-west of Charing Cross. It is historically a parish in the county of Middlesex that was incorporated as the Municipal Borough of Willesden in 1933; it has formed ...

.

London Underground

With traffic congestion on London's roads becoming more and more serious, proposals for underground railways to ease the pressure on street traffic were first mooted in the 1840s, after the opening of the Thames Tunnel in 1843 proved such engineering work could be done successfully. However, reservations over the stability of underground tunneling persisted into the 1860s and were finally overcome when Parliament approved the construction of London's first underground railway, the

With traffic congestion on London's roads becoming more and more serious, proposals for underground railways to ease the pressure on street traffic were first mooted in the 1840s, after the opening of the Thames Tunnel in 1843 proved such engineering work could be done successfully. However, reservations over the stability of underground tunneling persisted into the 1860s and were finally overcome when Parliament approved the construction of London's first underground railway, the Metropolitan Railway

The Metropolitan Railway (also known as the Met) was a passenger and goods railway that served London from 1863 to 1933, its main line heading north-west from the capital's financial heart in the City to what were to become the Middlesex su ...

. Begun in 1860 and completed in 1863, the Metropolitan inaugurated the world's oldest mass transit system, the London Underground

The London Underground (also known simply as the Underground or as the Tube) is a rapid transit system serving Greater London and some parts of the adjacent home counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and Hertfordshire in England.

The Undergro ...

; it was created by the cut-and-cover

A tunnel is an underground or undersea passageway. It is dug through surrounding soil, earth or rock, or laid under water, and is usually completely enclosed except for the two Portal (architecture), portals common at each end, though ther ...

method of excavating a trench from above, then building reinforced brick walls and vaults to form the tunnel, and filling in the trench with earth. The Metropolitan initially ran from Farringdon in the east to Paddington

Paddington is an area in the City of Westminster, in central London, England. A medieval parish then a metropolitan borough of the County of London, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965. Paddington station, designed b ...

in the west. The open wooden passenger cars were propelled by a coke-fueled steam locomotive and lit with gas lamps to provide illumination in the tunnels. The line was a success, carrying 9.5 million passengers in its first year of operation. An extension to the western suburb of Hammersmith

Hammersmith is a district of West London, England, southwest of Charing Cross. It is the administrative centre of the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, and identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London.

It ...

was built and opened in 1868. In 1884 the Metropolitan was linked with the Metropolitan District Line at Aldgate to form an inner circle encompassing Central London (the modern Circle Line), with a short stretch running from Aldgate to Whitechapel. In 1880 an extension line to the north-west was opened from Baker Street tube station

Baker Street is a London Underground station at the junction of Baker Street and the Marylebone Road in the City of Westminster. It is one of the original stations of the Metropolitan Railway (MR), the world's first underground railway, opened ...

to the village of Harrow, via Swiss Cottage

Swiss Cottage is an area in the London Borough of Camden, England. It is centred on the junction of Avenue Road and Finchley Road and includes Swiss Cottage tube station. Swiss Cottage lies north-northwest of Charing Cross. The area was ...

and St. John's Wood, expanding further over the coming decades and allowing prosperous suburbs to be developed around formerly rural villages.

A succession of private enterprises were formed to build new routes after the success of the Metropolitan, the first being the Metropolitan District Line, opened in 1865. This line extended along the Thames from Westminster to South Kensington

South Kensington is a district at the West End of Central London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically it settled on part of the scattered Middlesex village of Brompton. Its name was supplanted with the advent of the ra ...

at first, but by 1889 it had been extended eastwards to Blackfriars, and south-west all the way to Wimbledon

Wimbledon most often refers to:

* Wimbledon, London, a district of southwest London

* Wimbledon Championships, the oldest tennis tournament in the world and one of the four Grand Slam championships

Wimbledon may also refer to:

Places London

* W ...

.

The next line to be built, and the first true "tube", dug with a tunnelling shield designed by J. H. Greathead rather than by cut-and-cover excavation, was the City and South London Railway

The City and South London Railway (C&SLR) was the first successful deep-level underground "tube" railway in the world, and the first major railway to use Railway electrification in Great Britain, electric traction. The railway was originally i ...

(later the city branch of the Northern line), opened in 1890. It was London's first underground line with electric locomotives, and the first to extend south of the river. Electrification allowed the tunnels to be dug deep below ground level, as ventilation for smoke and steam was no longer necessary. In the year 1894, an estimated 228,605,000 passengers used the three underground railways then in operation, compared to 11,720,000 passengers in 1864 using the lone Metropolitan Railway. Before the century came to a close, a second deep-level tube was opened in 1898: the Waterloo & City Line. The shortest of the London tube lines, it was built to convey commuters between the City of London and Waterloo station.

Infrastructure

Roads

Many new roads were built after the formation of theMetropolitan Board of Works

The Metropolitan Board of Works (MBW) was the upper tier of local government for London between 1856 and 1889, primarily responsible for upgrading infrastructure. It also had a parks and open spaces committee which set aside and opened up severa ...

in 1855. They included the Embankment from 1864, Northumberland Avenue

Northumberland Avenue is a street in the City of Westminster, Central London, running from Trafalgar Square in the west to the Thames Embankment in the east. The road was built on the site of Northumberland House, the London home of the House ...

, Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell ( ) is an area of central London, England.

Clerkenwell was an Civil Parish#Ancient parishes, ancient parish from the medieval period onwards, and now forms the south-western part of the London Borough of Islington. The St James's C ...

and Theobalds Roads all from 1874. The MBW was authorized to create Charing Cross Road

Charing Cross Road is a street in central London running immediately north of St Martin-in-the-Fields to St Giles Circus (the intersection with Oxford Street), which then merges into Tottenham Court Road. It leads from the north in the direc ...

and Shaftesbury Avenue in the Metropolitan Streets Improvement Act 1877 ( 40 & 41 Vict. c. ccxxxv), the intention being to improve communication between Charing Cross, Piccadilly Circus